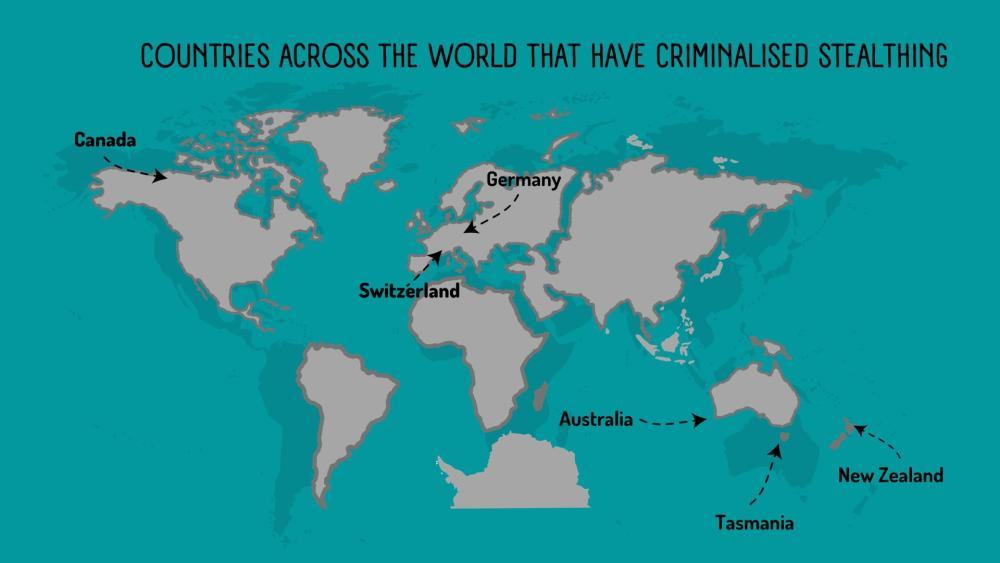

In recent years, the issue of ‘stealthing’ has gained attention as a concerning form of sexual misconduct. It should not be labelled as an emerging phenomenon though, as it consists of a practice that individuals have been engaging in for decades. The difference between then and now consists in the legal aspect of the act, now acknowledged in many countries as a crime.

Stealthing refers to the act of removing or tampering with a condom during sexual intercourse without the knowledge or consent of the partner, potentially exposing them to health risks, such as an unintended pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (Latimer et al., 2018). The phenomenon gained popularity due to it being tackled in a BBC limited TV series called I May Destroy You, produced in 2020 by actress/filmmaker Michaela Coel. Little academic research has been focused on this phenomenon, even if it belongs in the spectrum of sexual abuse, and more specifically that of rape. This is the case because victims-survivors of rape and stealthing share similarities when it comes to psychological and physical effects in the aftermath of the act (Shapiro, 2021). Their bodies are violated, they are in danger of unwanted pregnancies and STDs, their trust, body autonomy and dignity are shattered. Moreover, the most obvious similarity between rape and stealthing is the lack of consent involved in both acts.